The simplest rocket ever

This is a nice calculation on dropping balls stacked on top of each other; it was also an activity of my Postgraduate Certificate for Higher Education (PGCHE) in Birmingham. Many thanks to my Year 1 students for discussing this topic with me.

Material

Before we start, grab these things:

- Pen and paper.

- Two balls of different weights (like a basketball and a tennis ball, or a tennis and a squash ball, but any two bouncing objects would work).

Try it yourself

I hope you were able to find the balls. Now stack them on top of each other, with the light ball at the bottom and the heavy ball on top, and drop them.

If you couldn’t find the balls, this is what I meant:

Why is the small ball shooting up that fast?

The tennis ball is going much higher than what it would do if you drop it alone. Somehow, it’s being helped by the big basketball! As we will see, the big ball provides “fuel” to the small ball. And this is conceptually the same thing that happens in a rocket.

Key lesson

Today’s key concept is the conservation of energy and linear momentum. We believe these are among the most fundamental laws of Nature, at the backbone of our entire understanding of the physical world. Stacking balls is a neat example that shows them at play.

Setting up the stage

Let us recall that the kinetic energy of a particle of mass \(m\) and velocity \(v\) is

\[E = \frac{1}{2} m v^2.\]The particle’s linear momentum is

\[p = mv.\]In our case, we have two objects, so let’s indicate the mass of the big ball with \(M\) and that of the small ball with \(m\). Their velocities are \(v_M\) and \(v_m\).

Initially, both balls are falling down with the same velocity. Let’s call this \(v\). So, we start with both velocities directed downwards and

\(v_M = v_m = v\).

If you’re not sure why the two velocities must be the same, it’s time to revise the famous experiment by Galileo Galilei.

Two collisions

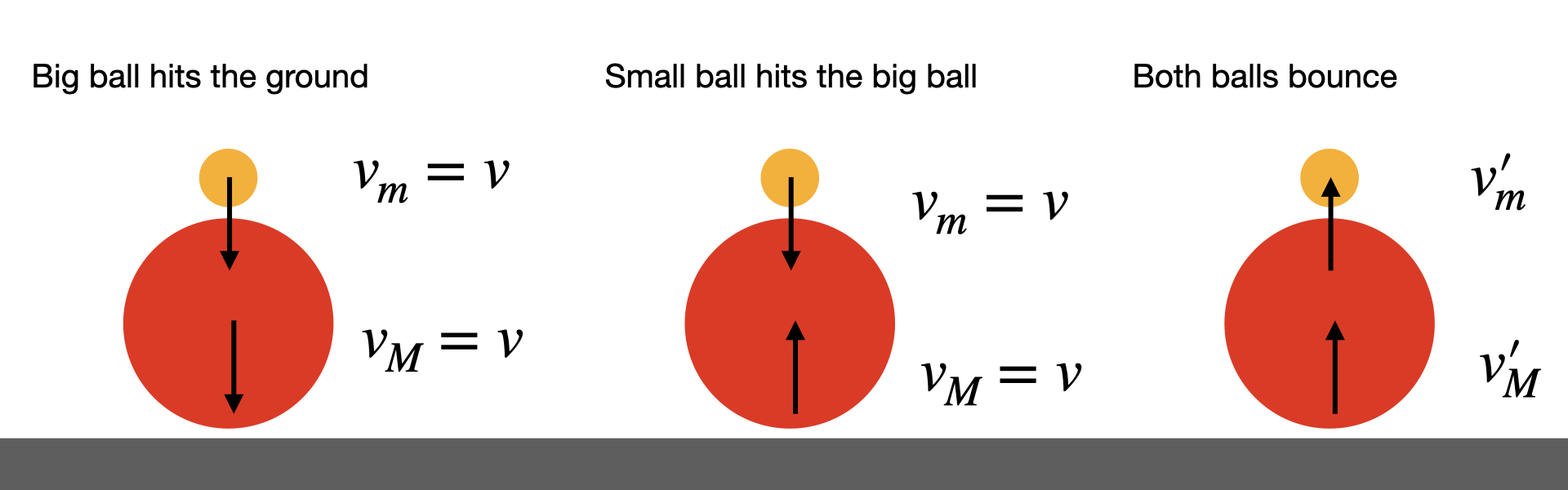

To understand why the tennis ball shoots up, we now need to track what happens to energy and momentum during the various collisions. Here is a schematic representation:

-

The first collision that takes place is that of the big ball and the ground

(Forget about the small ball for a second.) We can very safely assume that the mass of the Earth is much (much) bigger than the mass of the ball. In other words, the Earth does not move! If the Earth does not move, its linear momentum is obviously zero. That means that all of the linear momentum is in the big ball. Because linear momentum is conserved, the velocity of the big ball after hitting the floor must be the same as it had before, but is now directed upwards. So, still \(v\). -

Now the big ball is bouncing up while the small ball is still falling down.

\[\frac{1}{2} M v_M^2 + \frac{1}{2} m v_m^2 = \frac{1}{2} M v_M^{\prime 2} + \frac{1}{2} m v_m^{\prime 2}\]

We need to study the head-on collision between the two balls. The unknowns of the problem are the final velocities of the balls, let’s call them \(v'_m\) and \(v'_M\).

Here is where energy and momentum conservation become crucial. The energy before and after the collision must be the same:Linear momentum is also conserved:

\[M v_M - m v_m = M v'_M + m v'_m\]The minus sign in front of the second term is there because the small ball is going down, not up.

We know the velocities before the second collision (\(v_M = v_m = v\)) and we have two equations for \(v'_m\) and \(v'_M\).

Up to you now

Grab pen and paper and roll up your sleeves. Solve those two coupled equations. To simplify things, we are really only interested in \(v'_m\). You can find \(v'_M\) from one equation, plug it into the other, and derive \(v'_m\).

This activity should take you about 5 minutes.

Check your work

You should have obtained a second-degree equation for \(v'_m\). Second-degree equations have two solutions, which in this case are:

\[v'_m = -v\]and

\[v'_m = \frac{3M - m}{M + m} v.\]The first solution cannot possibly be right (can you say why? Hint: is the small ball going up or down in the experiment we started with?). So the second equation must be the physical solution. That’s how fast the small ball is shooting up.

Sum up

If the first ball is much more massive than the second one \(M \gg m\), the final velocity is close to

\(v'_m \simeq 3v\)

(Can you see why? Formally, this is a mathematical limit). The small ball goes up approximately three times faster!

In other words, the small ball is stealing some of the energy and momentum from the big ball. This is the same thing that happens in a rocket. Fuel is pushed down such that the capsules with the astronauts can gain energy and momentum and reach, say, the International Space Station.

More about rockets: you know they can steal momentum even from other planets? That’s called gravitational slingshot and it’s the only way rockets can reach the outer Solar System relatively quickly.

Stretching you further

Now, try to think about what happens if you were to put a third ball on top (you can try! Basketball + tennis ball + golf ball, but go outside or the golf ball will easily damage your ceiling!).

The second ball goes up three times faster than the first one, so the third ball must go up three times faster than the second one. That is nine times the initial velocity!

For one ball we have

\(v'_m \simeq 3v,\)

for two balls

\(v'_m \simeq 3^2 v = 9v.\)

Let’s stretch this further: if you imagine stacking \(N\) balls such that those at the bottom are always much heavier than those at the top, the final ball will receive a velocity

\[v'_m \simeq 3^{N-1} v.\]The velocity increases exponentially with the number of balls!

Can we really make a rocket out of this?

Yes! At least conceptually. To escape the gravitational pull of the Earth and reach outer space one needs a velocity of about 11 km/s (that is called the escape velocity; do you know how to compute it?).

Imagine we were dropping our balls from a height \(h\) of 1m. The velocity \(v\) with which they hit the ground is given by (again: energy conservation)

\[\frac{1}{2} m v^2 = m g h.\]The gravitational constant \(g\) is about 9.8 m/s², which means that the velocity \(v\) is about 4.5 m/s.

Now, plug this number into the equation we derived:

\[v'_m \simeq 3^{N-1} v\]For \(N=9\) the final velocity is about 30 km/s, which is enough to send the smallest ball out into space!

So: 9 balls on top of each other and you make a real rocket!

That’s a great idealized experiment, but back to reality now. Do you think this is really practical? Think critically about all the approximations we did that might invalidate the calculation.

And how about exploding stars?

This simple problem also has an exciting analogy with supernova explosions and exploding stars! Let’s finish this activity off with the video below. You see now why I said you shouldn’t try the three-ball experiment inside?